Carved by glaciers, shaken by tectonic forces, and reshaped daily by the world’s highest tides, the Fundy Trail in New Brunswick is more than a scenic drive, it’s a journey through 300 million years of Earth’s history. In this article, explore the science, landscapes, and personal moments that make this coastal route a must-visit for curious travelers.

1 A Fundy Trail Dream, Realized

I had heard of the Fundy Trail for years and seen photos of dramatic cliffs, sweeping coastal roads, and waves curling beneath foggy skies had lingered in my imagination. But it wasn’t until a cool, overcast day in May that I finally set out to see it for myself.

The drive from Saint John to the entrance took just under an hour, winding through the postcard-perfect village of St. Martins, where fishing boats rested on the ocean floor like fossils at low tide. The Bay of Fundy’s legendary tides were already putting on a show. They don’t just touch the coast, they transform it, draining entire harbours and pushing rivers backward twice each day.

Though commonly called the Fundy Trail, this spectacular route is officially known as the Fundy Trail Parkway, and it winds through the protected wilderness of Fundy Trail Provincial Park. It’s a place where science and scenery meet, where cliffs tell stories of ancient tectonic collisions, and the daily rise and fall of the ocean rewrites the shoreline in real time.

2 Quick Facts about the Fundy Trail Parkway

- Location: Fundy Trail Parkway, southern New Brunswick, Canada

- Trail Length: 30 km scenic drive through Fundy Trail Provincial Park

- Season: Open mid-May to mid-October

- Hours of Operation:

- Peak Season (late June to early September): 8:00 AM – 8:00 PM

- Shoulder Season (mid-May to late June & September–October): 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM

- Admission Fee: $18.76 CAD (2025 rate for resident vehicles)

- Park Features: Coastal cliffs, suspension bridge, hiking trails, lookouts

- Key Natural Features: Bay of Fundy tides, exposed bedrock, glacial erratics

- Geological Age: Bedrock formed ~300 million years ago (Pangea era)

- Nearest Towns: St. Martins, Sussex, and Saint John

- Operated By: New Brunswick Parks (Fundy Trail Development Authority)

3 From Ancient Pathways to the Fundy Trail Parkway

Long before the Parkway was built, this coast was known and used by the Mi’kmaq and Maliseet peoples, who fished, hunted, and traveled these lands for thousands of years. Their connection to this land remains, even if the interpretive signage doesn’t always tell their full story.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the area around Big Salmon River was a hub of logging and shipbuilding. Families like the Fownes and Melvins, prominent shipbuilders, owned significant portions of the land. Their family burial plots still exist along the parkway today .

Much of the land that now comprises the Fundy Trail Parkway was historically Crown land, managed by the province of New Brunswick. Over time, parcels were acquired or leased for various uses, including forestry and recreation .

The modern Fundy Trail Parkway was decades in the making. It began construction in the 1990s and was only completed in 2020, with a focus on balancing ecotourism and preservation. What could have been an overbuilt highway instead became a sensitive, scenic route that feels like it grew organically out of the coastline.

4 Into the Trail: A Drive Through Deep Time

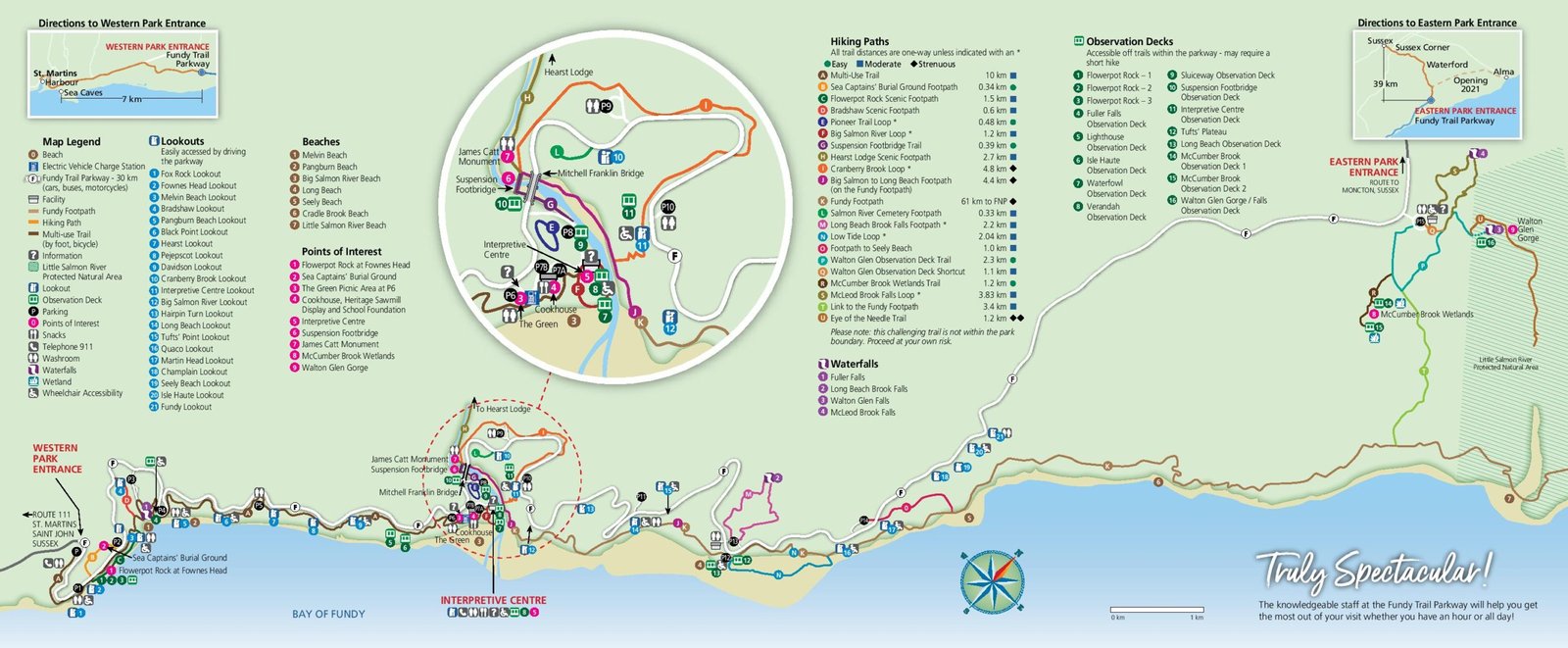

By 1:30 PM, I had reached the West Gate of Fundy Trail Provincial Park. After paying the entrance fee, I was handed a detailed map outlining scenic stops, lookouts, and hiking trail – a helpful guide for what was to become one of the most memorable drives of my life.

My first stop was Fownes Head, where the rugged coastline unveiled itself in full force. Sheer cliffs dropped into the Bay of Fundy, their ancient bedrock streaked with quartz veins, a testament to the tectonic violence that shaped this coastline over 300 million years ago. This wasn’t just scenic; it was textbook geology on display.

From there, I continued along the parkway, pulling over at several lookouts that each revealed a slightly different mood of the Bay of Fundy. The coastline here doesn’t repeat itself, but rather, it shifts, cliff by cliff, headland by headland, with each turn revealing a new geological layer or forested bluff.

Arrival at Salmon River

Eventually, I arrived at Salmon River – calm, green, and quietly powerful. I stood by the riverbank, looking out at the graceful suspension bridge spanning the water just upstream. From the river bank, I watched the tide push slowly inland, reshaping the shoreline with each wave.

Around me, a dense forest of spruce and fir framed the river, their roots anchored in the thin, acidic soil left by the glacier. The air was damp and quiet, the only sound the steady rhythm of the rising tide. I followed a short trail down to where the river meets the Bay of Fundy, a place where geology, ecology, and time seem to converge. It was the kind of place that encourages silence, where the land and sea whisper their ancient stories.

Lookouts, Solitude, and a View to Nova Scotia

At Salmon River Lookout, I found one of the quietest places I’ve experienced in Canada. Surrounded by trees and cliffs, the sounds of wind and waves were softened by the forest, just stillness and sky.

Farther along the parkway, I stopped at Quaco Lookout, where the view opened wide across the Bay of Fundy. From here, I could clearly see the distant shoreline and mountain ridges of Nova Scotia – two provinces separated by a bay that once began as a rift in a supercontinent.

There’s something profound about standing in one province and seeing another across the water, a geographic connection that emphasizes just how broad and deep this natural system really is.

Later at Martin Head Lookout, I stood mesmerized by the sight of the coast rolling away to the east, each ridge a wave of bedrock frozen in time.

5 Geological Story: Continental Collisions and Quartz Veins

The landscape of the Fundy Trail Parkway is more than beautiful, it’s a living archive of Earth’s restless history. Beneath the cliffs and coastlines lies a story of mountains born, continents torn apart, and glaciers that reshaped it all.

Collision and Mountain Building

The cliffs along the Fundy Trail Parkway aren’t just scenic, they’re a cross-section of deep time, exposed by tectonic forces and human engineering alike. Much of the exposed rock here is basalt, a dense volcanic rock, but its origin reaches far deeper into Earth’s history.

Roughly 300 million years ago, during the late Paleozoic, the Earth’s continents were colliding to form the supercontinent Pangea. New Brunswick was caught at the heart of this collision as North America, Africa, and Europe converged. The result was a massive chain of mountains, ancestral to the present-day Appalachians and created by the intense pressure, folding, faulting, and uplift of crustal material.

Today’s Fundy coastline preserves these ancient scars in the form of tilted rock layers, fractured cliffs, and complex mineral patterns, all records of a time when continental crust was pushed to its limits.

The Rift Valley That Became the Bay

After Pangea reached its peak, the tectonic script flipped. Around 200 million years ago, during the Triassic and Jurassic periods, the supercontinent began to break apart. As tectonic plates pulled away from one another, the crust in some regions began to stretch and thin, forming deep linear depressions known as rift valleys.

The Fundy Basin is one such rift valley – a geologic fault zone that began to open but never evolved into a full ocean basin. Instead, it stalled partway through the process, leaving behind a dramatic, steep-sided valley that eventually filled with seawater as the Atlantic Ocean continued to widen nearby. Today, we know it as the Bay of Fundy.

This stalled rifting explains the Bay of Fundy’s extraordinary depth, steep coastline, and elongated shape and why the tides here are so extreme. The geometry of the Fundy Basin acts like a natural amplifier, resonating with the lunar tidal cycle to produce the highest tides on Earth, with differences of over 12 meters (40 feet) between low and high tide.

Quartz Veins and Volcanic Clues

Look closely at the road cuts and exposed cliffs along the Parkway, and you’ll notice something striking: white quartz veins slicing through the darker volcanic rock. These were formed when hydrothermal fluids, rich in silica, flowed through cracks in the rock caused by tectonic stress. As the fluids cooled, they crystallized into ribbons of quartz.

These quartz veins are among the most visible signs of the tectonic and thermal activity that shaped the Fundy region. They serve as visual reminders that the Earth’s crust was once molten, fractured, and alive with motion, far below the ground we now walk.

A Shared Geologic Heritage

As I stood overlooking the basalt cliffs, I was reminded of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco – a place I had visited years earlier. Though separated by an ocean and thousands of kilometers, these landscapes share a common tectonic origin. Both were formed by the same continental collisions that created Pangea and later shaped its destruction.

In that sense, New Brunswick and Morocco were once geological neighbors, connected by a landmass that no longer exists. The Atlantic Ocean didn’t just separate continents, it unzipped a shared story, leaving fragments on either side that now speak quietly of the same ancient past.

Glacial Legacy: The Last Ice Age’s Imprint

The geological story of the Fundy Trail Parkway doesn’t end with rifting and mountain-building. The most recent chapter was written in ice.

During the last Ice Age, the entire region was buried beneath the massive Laurentide Ice Sheet, which reached its maximum extent around 20,000 years ago. As it advanced, the glacier scraped and scoured the landscape, stripping away topsoil, carving valleys, and reshaping rivers.

When the ice finally began to retreat around 12,000 to 10,000 years ago, it left behind a transformed terrain—thin soils, u-shaped valleys, and scattered glacial erratics. These large, rounded boulders were picked up by the moving ice and dropped far from their origin.

At Salmon River, I noticed granite rocks in shades of pink and red that clearly didn’t match the local basalt bedrock. These out-of-place stones had been transported here by ice – a visible, tangible reminder of the glaciers’ immense reach.

Even the coastal forest reflects this legacy. With rich soils scraped away, hardy species like spruce and fir dominate the landscape, adapting to the lean, acidic soils left behind. In many ways, the Fundy Trail is not just a monument to tectonic upheaval, it’s also a quiet museum of the glacial past.

6 The Climate and Forest of the Fundy Coast

The cool, moist climate of the Bay of Fundy isn’t an accident, it’s the product of both local geography and global ocean circulation. Cold waters that shape this coastline originate far to the north in the Arctic Ocean, traveling southward along the eastern Canadian seaboard as part of the Labrador Current. By the time these waters spill into the Bay of Fundy, they bring not just a chill, but also dense, moisture-laden air that helps generate the region’s frequent fog and cool marine climate.

This oceanic influence acts like a natural thermostat, cooling summers and moderating winters and contributes to high humidity and narrow seasonal temperature swings. Fog is especially common in late spring and early summer, when cold air over the bay meets warmer inland air masses. These conditions create a coastal microclimate that’s damp, cool, and shaded for much of the growing season.

But it’s not just the weather that shapes this landscape, it’s the soil, or lack of it. During the last Ice Age, glaciers scraped the bedrock clean, leaving behind thin, acidic, poorly drained soils. In this marginal terrain, spruce and fir forests dominate. These conifers are adapted to short growing seasons, poor nutrients, and exposed, wind-swept slopes. Their roots cling to fractured rock, and their dark green needles photosynthesize in low light- an evolutionary answer to cold, cloud-heavy skies.

Under this evergreen canopy, mosses, ferns, and lichens thrive in the filtered light and near-constant moisture. You’ll see little of the dense underbrush found in warmer or more fertile regions; instead, this is a forest of subtle resilience, thriving not in spite of adversity, but because of it.

The result is a landscape that feels ancient and quiet, a forest shaped as much by Arctic currents and glacial scars as by the trees themselves. The beauty here is not in lushness or color, but in endurance, and in the way nature adapts to the slow, powerful rhythms of the planet.

7 Practical Tips for Visiting the Fundy Trail Parkway

- Best Season to Visit: Late May through early October offers the best mix of weather, open facilities, and accessible trails.

- Park Entry Point: The West Gate is closest to the village of St. Martins – about a one-hour drive from Saint John.

- Admission: $18.76 CAD per vehicle for New Brunswick residents as of 2025. Prices may vary slightly for non-residents.

- Facilities: Washrooms, picnic areas, and seasonal canteens are available at several stops along the parkway.

- Hiking Access: Numerous well-marked trails run along the coast and into the forest, ranging from short lookouts to longer ridge hikes.

- Connectivity: Cell service is limited in many areas, so you can download offline maps or the park’s official app before arrival.

- Visitor Map: A detailed park map is provided at the entrance gate and is useful for planning stops and trails in advance.

- Visitor Information Centres:

- Big Salmon River Interpretive Centre (West side): A heritage-style centre near the western gate with exhibits on local logging and shipbuilding, plus access to a historic sawmill and cookhouse.

- Walton Glen Gorge Interpretation Centre (East side): Near the eastern gate, this centre features displays on Fundy’s ecosystems and serves as a starting point for trails to the Walton Glen Gorge.

8 Pro Tips for the Science Traveler

- Spot Glacial Erratics: At Salmon River and other locations, look for large granite boulders that don’t match the local rocks carried here by glaciers thousands of years ago.

- Watch the Tides in Action: Visit a river mouth like Salmon River at low tide and stay to watch the rising tide push inland – a live display of Fundy’s extreme tidal forces.

- Trace Quartz Veins in Basalt: At several road cuts and lookouts, inspect the exposed bedrock for white quartz veins, formed by mineral-rich fluids during tectonic activity.

- Compare Coastal vs. Inland Forests: Note how spruce and fir dominate near the coast due to poor, acidic soil, while hardwoods appear further inland where soil is deeper.

- Ask the Experts: Don’t hesitate to speak with park staff at the Visitor Information Centres. They often have great insight into seasonal geology, tide timing, and lesser-known features.

9 Final Reflections: Coastal Time Travel

My afternoon on the Fundy Trail was more than a scenic drive. It was a journey into the geological forces that shaped our planet, into the rise and fall of tides that continue to sculpt the coast, and into the quiet memory of glacial giants that once ruled here. You don’t need to be a scientist to feel the gravity of this place. But if you are, even just a curious one, this is a masterclass in Earth’s ancient rhythms.

I’ll be back.

10 More Science Travel Adventures

If you enjoyed this journey through the geology, tides, and forests of New Brunswick’s Fundy coast, you might also like: