On the rugged coast of Nova Scotia, where the world’s highest tides meet ancient cliffs, the Joggins Fossil Cliffs reveal a story over 300 million years old. Here, fossils of towering swamp forests and early land life are exposed daily by the Bay of Fundy. As a science traveler, I came to walk this UNESCO World Heritage Site – tracing time layer by layer, where Earth’s prehistoric past still lies in plain sight.

1 The Journey to Joggins Fossil Cliffs

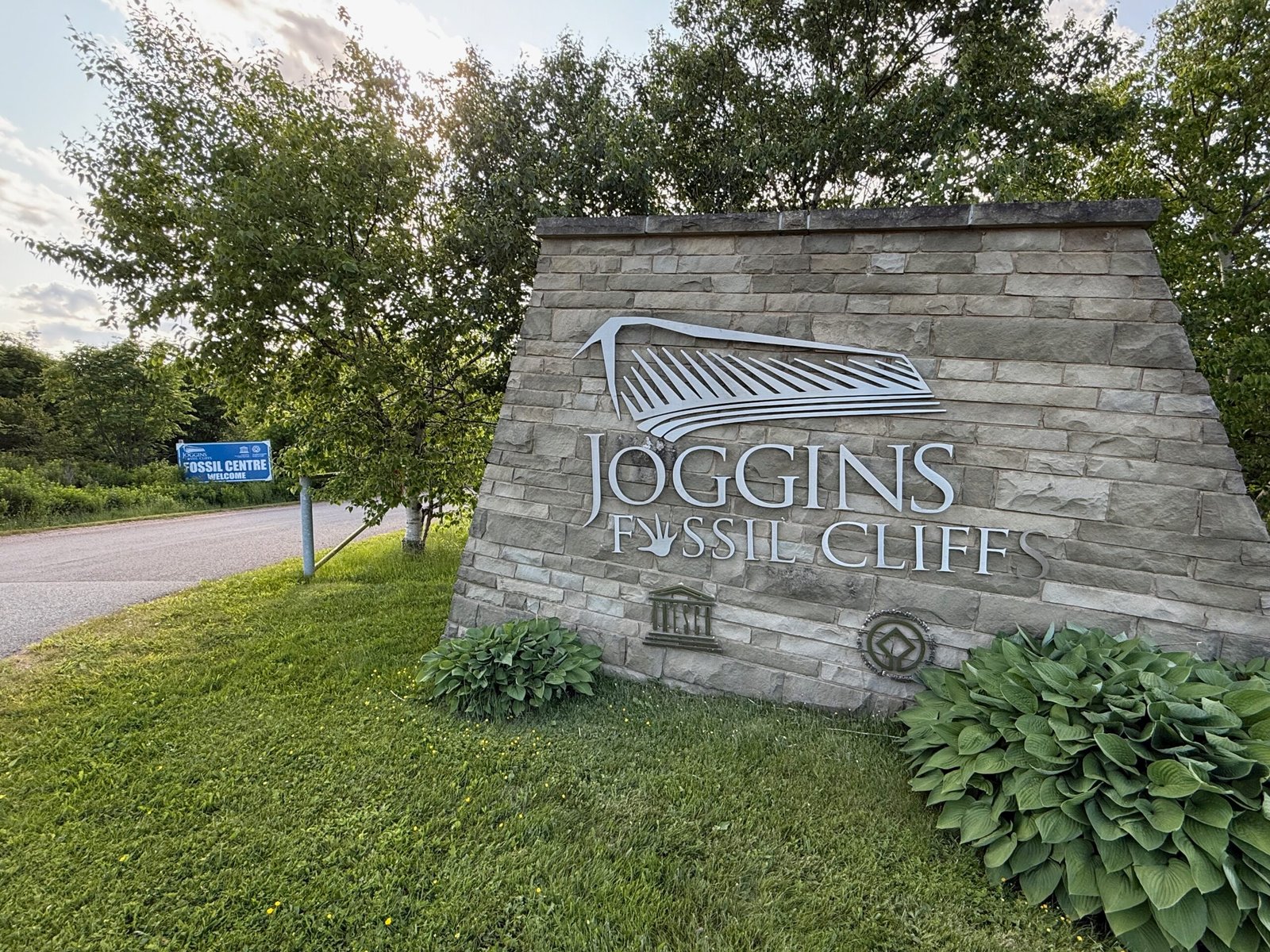

On a sunny June afternoon, I left Saint John, New Brunswick, and drove three hours east to a place I’d been dreaming about visiting for years: the Joggins Fossil Cliffs. As I wound through the quiet roads of Nova Scotia and finally approached the coast near Amherst, I couldn’t help but feel a growing sense of anticipation.

I’d read that the cliffs here preserve one of the richest fossil records of life on land from over 300 million years ago – a time long before dinosaurs, when strange forests and the earliest reptiles thrived. But reading about it and seeing it are two very different things. What I didn’t know that day was just how alive this ancient place would feel.

2 Quick Facts

- Location: Near Amherst, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Setting: On the Bay of Fundy, home to the world’s highest tides

- What it is: A 14.7 km stretch of cliffs and beach exposing fossils from the Carboniferous Period (~315 million years ago)

- UNESCO Status: Designated a World Heritage Site in 2008 for its exceptional record of life on land during the Carboniferous

- Fossils found here:

- Lepidodendron (giant “scale” trees)

- Sigillaria (slender, scaly trees)

- Calamites (giant horsetails)

- Stigmaria (root systems)

- Carbonicola (freshwater bivalves)

- Early reptiles & amphibians

- Best time to visit: At low tide, when the beach is fully exposed

- Visitor centre: Open seasonally, with exhibits and guided tours

- Admission: ~$10–12 adults; discounts for seniors, students, and families. Beach access free

- Hours: Daily, May–October, ~10 AM–5 PM (closed in winter)

- Fossil rules: Removing fossils is prohibited without a permit — take only photos

3 First Steps Back in Time

When I arrived, the late-afternoon sun cast a golden light on the cliffs, and the Bay of Fundy shimmered in the distance, its waters here a distinctive chocolate brown, coloured by the muddy tidal flats and the silt-rich flow of the Petitcodiac River from the north. The visitor centre sat on a rise overlooking it all – a small but modern building that serves as both museum and gateway to the site.

Inside, you can pay a modest fee to see their displays of fossils and learn about the history of the cliffs. But my excitement to explore was too strong to resist. I decided to head straight for the beach – a 14.7-kilometre stretch of rocky shore where time seems to unravel with each step.

Descending the stairs, I paused at the landing and immediately noticed something delightful: visitors before me had set out an impromptu fossil display on the rocks – little treasures they’d found and admired but respectfully left behind. I was struck by the sheer variety. Among them was a gorgeous chunk of Lepidodendron, also known as a “scale tree,” its bark still showing the diamond-shaped patterns of a long-vanished forest giant.

That’s when it hit me: this wasn’t just a beach, it was a gallery of Earth’s memory, laid bare for anyone willing to look.

4 The Rhythm of the Bay

Before I go further, here’s an important tip: if you’re planning your own visit, check the tide tables. The Bay of Fundy has the highest tides in the world – rising and falling as much as 15 metres (50 feet), and at high tide, much of the beach disappears. I timed my visit for low tide, which left me hours to roam the exposed beach and marvel at its treasures.

And there were plenty.

5 A Fossil Hunter’s Paradise

The cliffs themselves are spectacular: stratified layers of rock stacked at a steep angle, each band a different shade of grey, red, or black. These layers were laid down by rivers and swamps during the Carboniferous Period – about 315 million years ago, and then tilted by the shifting of Earth’s crust.

I started my exploration by walking south along the beach, which I later learned was the direction of “younger” rock layers. Heading north takes you deeper into the past.

At the base of the cliffs, where erosion from wind, rain, and tide constantly exposes new material, the fossils practically announce themselves. My first find was a slab of rock etched with the distinctive ridges of Lepidodendron bark. These ancient lycopsids were tree-like plants that grew up to 30 metres tall in swampy forests and left behind patterns so characteristic you feel like you’re touching history itself.

As I walked further, the cliffs revealed more secrets: segments of Calamites, giant horsetail plants with their hollow, jointed stems fossilized in the mud of ancient floodplains. Some were flattened into the shale, their segmented ribs like a ladder pressed into stone, while others retained more of their cylindrical shape, broken off and protruding slightly from the surrounding rock. In one piece, multiple stems crisscrossed at odd angles, as if frozen mid-collapse in some ancient flood.

Near one of those coal seams, I found what I believe was Carbonicola – small, shiny bivalve shells pressed into the shale like delicate fingerprints, clustered together in a dark, carbon-rich slab. These freshwater mussel-like creatures thrived in the brackish ponds and swamps above and below the coal seams, their shells now embedded in a rock that still carried the faint sheen of coal.

Later, a piece of rock left on display at the stairs to the beach by another visitor caught my eye for its honeycomb-like surface. It turned out to be Sigillaria, another giant lycopsid with a more slender trunk than Lepidodendron, its bark patterned with a neat lattice of leaf scars. Nearby, I noticed another distinctive texture: a block of Stigmaria, the fossilized root of one of these massive lycopsid trees. Its surface was covered in rows of circular scars where the fine rootlets had once spread into the mud, giving it a knobby, almost alien appearance.

Everywhere I looked, the beach seemed to offer a new glimpse into this long-lost world – ribbed Calamites, knotted Stigmaria, delicate Carbonicola, and more, each fossil a fragment of the swamp forests and shallow waters that covered this place 315 million years ago.

6 The Power of Preservation

What makes Joggins truly remarkable is how dynamic it is. The Bay of Fundy’s tides – relentless and powerful, scour the base of the cliffs twice a day, constantly eroding them and uncovering new fossils. It’s no wonder scientists and visitors alike keep returning.

And yet, despite the bounty, the cliffs are fragile. Fossil collecting here, or anywhere in Nova Scotia, requires a permit. I felt grateful that previous visitors had left their finds on the rocks for others to see, creating a shared experience rather than stripping the site bare.

7 A Place Like No Other

After walking south for some distance, I turned and headed north along the beach. I noticed that the fossils were less frequent on this stretch, but the layers of rock were even more dramatic. I felt like I was walking deeper and deeper into time itself, back toward the dawn of life on land.

By the time I made my way back to the stairs, the sun was beginning to dip toward the horizon, painting the cliffs in soft oranges and pinks. The tide was already creeping back in, claiming the beach one wave at a time.

Standing there, I felt both awed and humbled. The sheer abundance and variety of fossils here – plants, roots, shells, brought the Carboniferous swamp vividly to life in my imagination.

I had spent hours exploring and barely scratched the surface.

8 Practical Travel Tips

Planning a visit to the Joggins Fossil Cliffs is straightforward, but a few preparations will help you make the most of your time here:

- Check the tide tables: Plan your visit for low tide – the beach is at its widest and the fossils easiest to spot.

- Wear sturdy footwear: The rocky beach is uneven, with loose stones and slippery surfaces.

- Dress for the weather: The Bay of Fundy coast can be windy and cool, even in summer.

- Allow plenty of time: Give yourself at least a couple of hours to wander both the museum and the beach.

- Bring cash or card: The museum has a small admission fee, which supports conservation and research.

- Parking is free: But in peak season, it can fill up, so arrive early if you can.

9 Pro Tips for the Science Traveler

If you’re visiting with an eye for the science and history of the cliffs and want to appreciate their full significance, keep these in mind:

- Start south of the stairs: The southern stretch of beach had the most visible and diverse fossils during my visit.

- Brush up on the Carboniferous Period: Knowing a little about the ancient swamp forests, lycopsids, and early reptiles makes the fossils come alive.

- Look near the cliff base: Fossils are most often exposed where erosion is freshest, near the base of the cliffs.

- Take photos, not souvenirs: Fossil collecting here is prohibited without a permit, but photography is encouraged.

- Observe the layers: Notice the colors and angles of the strata, as they tell the story of shifting rivers, swamps, and tectonic forces over millions of years.

- Visit the museum first: The exhibits will help you identify what you’re seeing out on the beach.

- Keep notes or sketches: It’s easy to forget what you’ve seen when surrounded by so many fossils and features.

10 Final Reflections

Walking along the Joggins Fossil Cliffs felt like walking through time. To touch the bark of a tree that grew before dinosaurs existed; to see the roots of a swamp forest preserved in stone, is to connect with a world unimaginably old and yet somehow familiar.

If you’re a science traveler, Joggins is not just a destination – it’s a journey into Earth’s memory, written layer by layer, waiting for you to read it.

And like the tide, I know I’ll return.

11 More Bay of Fundy Adventures

If you enjoyed this article, explore these other science travel stories from around the Bay of Fundy: